SOLVING FOR X: 'God Loves, Man Kills' Through the Lens of Now

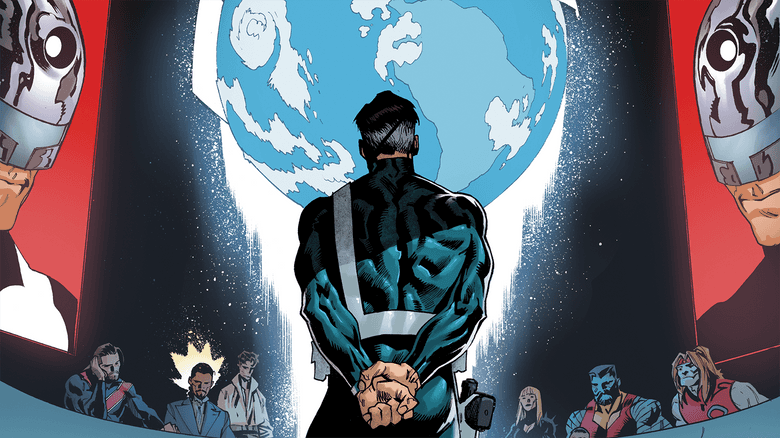

Revisiting Chris Claremont and Brent Anderson's influential X-Men story three decades later.

Editor's Note: Chris Claremont and Brent Anderson’s influential X-Men story is re-presented in a two-part Extended Cut with all-new pages from the legendary creators themselves. The comics are products of their time, portraying the prejudices and discrimination that were commonplace in American society through an X-parable. The essay that follows will examine humanity and its injustices, being a minority, the atrocities committed, and its relevance to the current moment today, almost four decades after the story was first published. Issue #1 is available in comic shops now.

Written in 1982 by legendary X-MEN scribe Chris Claremont, GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS uses the prestige format of the graphic novel to interrogate social issues around identity, faith, and fear. Although the story is very much an artifact of its time, the core messages that Claremont and artist Brent Anderson brought to life are just as resonant today as they were 38 years ago. Claremont is a master at using characters to solve and explore real-world problems, and this graphic novel is a prime example of that.

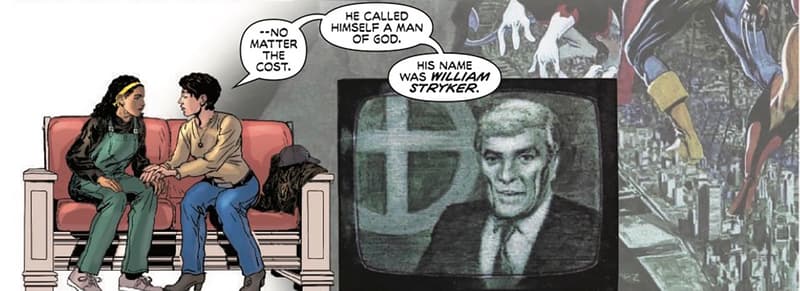

Whether it’s gender, religion, race, or the wearing of masks, mankind has historically legitimized the oppression of “the other.” Historically, “the other” is treated in three major ways—by distancing the other, making the other more like oneself, or trying to destroy the other. The main antagonist in GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS, Reverend William Stryker (Stryker), decides to do the latter and uses the powerful tools of religion and faith to justify his crusade to rid the world of mutantkind including our heroes, the Uncanny X-Men. That’s the central conflict of GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS.

Stryker uses his faith as a weapon against mutants in order to deal with the anguish of losing his family, but also to deal with the fact that his child was born a mutant. The internalized self-hate and fear needed a place to live, and Stryker twists the peaceful and unifying edicts of Christianity to legitimize his bigotry. However, this isn’t a new idea. Religion has been used as a tool to justify enslavement and inspire liberation throughout history. Claremont, a man of faith himself, clearly understands this and creates a riveting narrative that explores this in spectacular fashion.

[RELATED: Why 'God Loves, Man Kills' Is One of the Best X-Men Stories Ever]

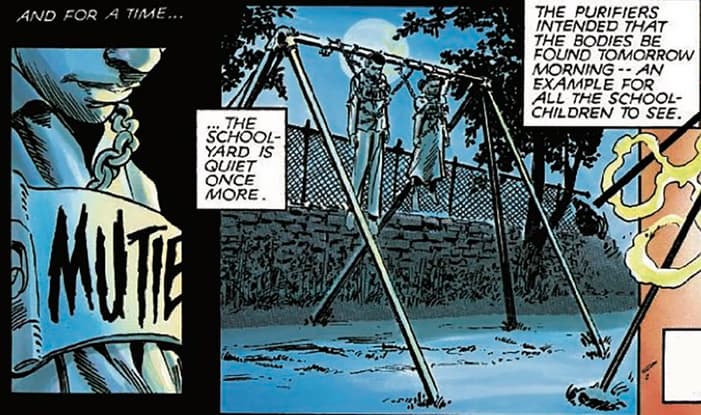

Critiquing how mankind uses religion is only one aspect of the story. One other metaphor that has always been under the skin of the X-MEN, going back to the book’s origins with Stan Lee and Jack Kriby, is the idea of race. To be frank, the inciting incident of GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS is a lynching. In the opening sequence of the story, two mutant children, 11-year-old Mark and 9-year-old Jill, are fleeing a tactical squad that works for Stryker called the Purifiers. It is not lost on the reader that these two siblings are Black mutants. And it is, therefore, easy to see the parallels related to race and racism in America. It’s apparent in this story in groundbreaking-for-its-era ways that had previously been alluded to, but never as loudly spoken.

When Jill asks the Purifiers, “Why,” the leader of this racist sect simply states, “Because you have no right to live.” The Purifiers explicitly tell these two Black mutant children that they do not matter and deserve to die because of who and what they are; “the other.” Right before Jill asks her last question, we see a cold moonlight blue panel with her brother Mark’s blood on her hand. The bright red color is a poignant reminder that we are all the same; that we bleed the same blood. However, the Purifiers, in their zealotry, only see the other that they must destroy at all costs.

The bodies of these two children are left hanging from a swing as a warning or message to, presumably, other mutants. A sign saying “MUTIE” is left to “out” the Black children who passed as human. In Chris Claremont’s X-MEN, the slur “MUTIE” has come to represent for many, all racial, ethnic, homophobic and xenophobic slurs that strive to “other” whole groups of people. It stands for all oppressed people of the world. This marking of “the other” has always been an important step in dehumanization.

Throughout this story and his writing, Claremont’s X-MEN tackled identity issues head on. That’s one of the reasons this story is one of the most enduring and respected in the history of the franchise and has even inspired one of the most critically-acclaimed Super Hero films of all time: X2: X-Men United. The idea of “the other” allows everyone to see themselves, in some way, in one or more of the characters. However, in GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS, it is clear Claremont has chosen to openly explore the notions of race through the allegory of mutation.

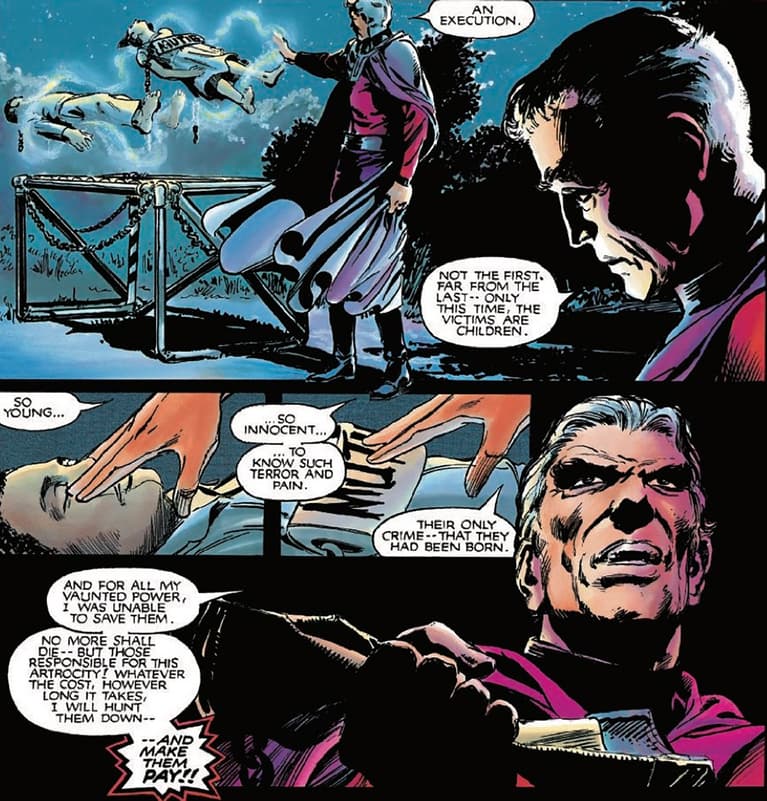

Throughout history, the deaths of Black people, and the disruption of our lives, have historically been a rallying cry for all Americans, regardless of race, to rise to the call of social justice. In GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS, we witness this in the moment Magneto finds the children before they are seen by others. Jill and Mark become martyrs in Magneto’s mission to stop Stryker, and this moment makes him more resolute in his beliefs.

Whether it is the original sin of chattel slavery and its abolition, water hoses being turned on Black Civil Rights protestors on live television in the 1960s leading to buses of young people traveling to the South, or the photos of the mutilated remains of 14-year-old Emmett Till that helped power the Civil Rights Movement move forward, Black deaths are part of American history and social change. Right now, even more history is being made on the streets of our country as the result of the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Jah’Sean Hodge, George Floyd and so many others.

The story's parallels to "now" do not end within the first few pages. Claremont sets out to make an evergreen story inspired by this kind of social change, but he also makes a point to show us that this kind of change isn’t easy.

As a result, he doesn’t let readers escape the brutality of our society and wasn’t afraid to show the messiness of our humanity. He even uses the racially-charged “N-word” in GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS via the mouth of one the most beloved X-Men—the young and plucky Kitty Pryde. While she uses the slur to make a point to her Black dance instructor Stevie, it is not without its problems. Kitty equates the idea of “Mutie” to the “N-word,” a well-meaning sentiment. However, she, like most of the classic X-Men team, can easily pass for a “human” and are phenotypically white. Because they aren’t perceived as different, that analogy doesn’t map well onto how racism is constructed. Stevie states that while Kitty is right to feel as she does; she, a white teen, will never experience the trauma of racism that Stevie has endured and will continue to endure until we end systemic racism.

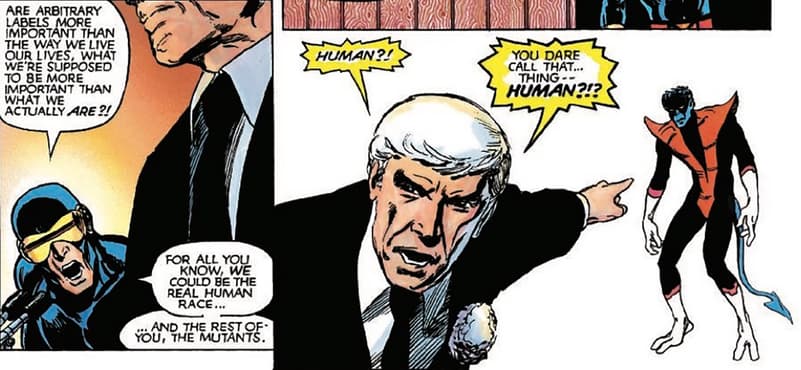

Despite its flaws, GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS is timeless. It gives us the essence of every main character, and is a complete and transformative story that touches on each of their strengths and nuances, including intellect. While there is a lot of action in the story, the final conflict—one of my favorite moments—between Cyclops and William Stryker is a battle of ideas. Cyclops’ passion, beliefs, and singular vision win the day philosophically, and it is a defining moment for that character. Perhaps I'm biased; Cyclops is my favorite of the X-Men.

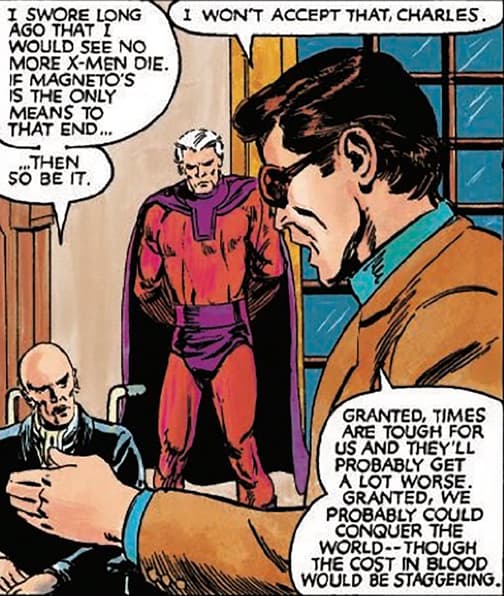

In addition, no character is left unaffected, even the brilliant Professor Charles Xavier. In a crisis of faith, a tearful Professor X considers abandoning his beliefs to join forces with his old friend and more radical adversary Magneto. I recognize those tears; I’ve cried them myself of late. They are the tears of a father who knows that he can’t always protect his children and that he has limitations.

For me, these tears are also tears of pride. Pride in knowing that he can depend upon the next generation of mutants to push forward and hopefully see a better world. Despite all the horrible things that can happen on any given day, there is a need for this kind of hope.

In the final conversation between Cyclops and Storm, the story cements that hope and its complexity. Cyclops alludes to love “making the world go ‘round,” and Claremont gives Storm the final and possibly most impactful words of the story and character development, “If only that were so.” As a Black woman and a mutant, as well as her character understanding and personal experience of homelessness and poverty, Storm sits on more crossroads than any other X-Men in the story. Storm intimately knows that, in spite of faith, the future is unknown and progress is uncertain.

That final message from GOD LOVES, MAN KILLS continues to resonate in this current moment in American history. And I, like Storm, am cautiously hopeful that with a little luck, a lot of understanding, and more hard work in dealing with the systems that divide us, perhaps we can do more than simply survive. Maybe we can achieve Professor X’s dream and figure out how to truly live together.

JOHN JENNINGS is an Eisner Award-winning scholar and artist and is a New York Times best-selling author for his artwork on the graphic novel adaptation of Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred. Jennings is also a professor of media and cultural studies at the University of California, Riverside and is founder and curator of Abrams Megascope, a new line of books from Abrams ComicArts that focuses on primarily speculative graphic novels by and/or about people of color.